Ian Widgery reflects on the past eight years since he redefined the sound of jazz-age Shanghai and pioneered a global craze.

Seventy-eight RPM vinyl records and curious-looking wax cylinders imprinted with the voices of some of China’s most legendary and talented songstresses—Bai Guang, Zhou Xuan, and others—sat, crated for decades, in a dusty Mumbai warehouse. Leftover goods from the former Pathé recording studio in Singapore, they were slated for disposal until being diverted to EMI Music’s Hong Kong offices in 2003 when the company was preparing to commemorate its one-hundredth anniversary in China.

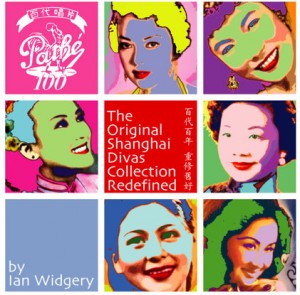

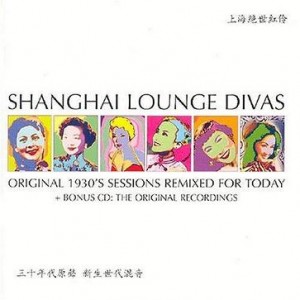

Enter Ian Widgery, a young UK music producer, also newly arrived to Hong Kong. Collaborating with Morton Wilson, founder and president of Schtung Music, Widgery remixed twelve popular pre-1949 Chinese songs, such as “Waiting for You” and “Nighttime in Shanghai,” within the span of a few short months, creating Pathé 100: The Original Shanghai Divas Collection: Redefined. The first album of its kind to revitalize and introduce this early popular Chinese music to audiences worldwide, it has been reissued countless times in the past eight years, including the essential Shanghai Lounge Divas two-disc compilation featuring Widgery’s remixed tunes and a set of twenty-four original recordings of songs from pre-1949 Shanghai. The “Divas project,” as Widgery fondly refers to it, went platinum for the fifth time in 2010. Since 2003, Widgery and Wilson have teamed up for two more successful projects: Retrochine (2008), a journey through the catalog of Hong Kong’s Shaw Studios, and the Shanghai Tang Lounge Collection (2010), an album featuring original and remixed music for the Chinese fashion house Shanghai Tang.

Was it all a matter of destiny? Looking back at the past eight years, Widgery describes the incredible and unexpected outcomes that began unassumingly enough with a set of old, abandoned recordings.

Shanghai Divas

“It was so different from anything that I had ever heard before,” says Widgery of the first time that Wilson played a sampling of songs from the recovered Pathé recordings for him. “I had no idea what it was about.” Without translations for the lyrics—or even the titles of the songs—he went straight to work remixing the songs, feeling the language of the arrangement and the emotion expressed in the voices of the singers as he went along. “I decided one day just to put it in the sampler and to start writing songs around the melodies,” he explains.

“It was so different from anything that I had ever heard before,” says Widgery of the first time that Wilson played a sampling of songs from the recovered Pathé recordings for him. “I had no idea what it was about.” Without translations for the lyrics—or even the titles of the songs—he went straight to work remixing the songs, feeling the language of the arrangement and the emotion expressed in the voices of the singers as he went along. “I decided one day just to put it in the sampler and to start writing songs around the melodies,” he explains.

The material Widgery was working with was, in fact, the stuff of legends. Republican era (1911-1949) Shanghai was famous worldwide as a glamorous, glittering city with burgeoning music and film industries full of famous women. During the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), China’s last imperial dynasty, public female performances had been largely taboo, and so the women entertainers of Shanghai’s “golden age” were a radical departure from Qing dynasty ideology.

Women such as Bai Guang, the femme fatale of her day, in fact, helped to define the elegant and cosmopolitan lifestyle idealized by the everyday women of Shanghai. The products consumed by Shanghai’s residents and the popular culture of the city—not least of all the music—bear the unmistakable mark of influence from the United States and Europe. But with as much veracity as Shanghai housewives read about the lives of Hollywood film stars and American jazz tunes were played in dance halls, most of the films and music produced in Shanghai were an exploration and a creative adaptation of Western popular culture in keeping with Shanghai’s cosmopolitan atmosphere, rather than outright imitation.

In this same way, Widgery and Wilson’s remixed tracks are a masterful merging of pre-1949 music with electronica—a redefinition of the music that defined the sound of jazz-age Shanghai. The vocals on the tracks emerge, distant- and dreamy-sounding through swathes of beats that enhance, but do not stifle the essence of the songs. For example, Widgery crafted “Waiting for You” into a downtempo masterpiece that retains Bai Guang’s trademark low voice, evocative of both a jazz-age cabaret and a contemporary lounge.

Widgery remixed a few of the songs in Hong Kong before moving to Vancouver, Canada to be married and to settle down. “I ended up putting together the rest of the tracks outside on a computer on a lawn in Canada,” he laughs. He returned to Hong Kong to finish the album with Wilson, a process that was completed within a matter of months. “I have worked on over seventy projects,” he says, “but never on a project that has been able to be produced so quickly . . . In a way, I was so inspired by what was going on, that it really wrote itself. That is a sign of a good project.”

Shanghai Lounge Divas has proved to be so successful worldwide that Widgery is not only gratified, but even a little astounded by it all. Several of the songs have been licensed for use in films, and only a few years ago, Annie Lennox, speaking on television with Jools Holland, enthusiastically praised the album, calling it the “most fantastic thing.” Elton John was also spotted purchasing thirty-five copies of the album at an EMI store. Most importantly though, the Divas project has brought the voices of Bai Guang and her contemporaries to listeners from a different generation and to places where the music might otherwise never have been heard. Shanghai Lounge Divas has inspired imitations, but none as enduring as it. “It just keeps going and going,” emphasizes Widgery. “I am so happy for the fact that all of this music is out there for younger people from different cultures to be exposed to.”

Retrochine

Following the success of Shanghai Lounge Divas, the Shaw Brothers Studios in Hong Kong—perhaps best known for its early martial arts films—approached Widgery and Wilson in 2008 about doing a remix album featuring songs from their catalog of musical films. Although the resulting album, Retrochine, is in a vein similar to that of the Divas project, its fifteen tracks cover a slightly later era—the 1950s and 60s—and a completely different and unique region of China. “We wanted to do an album that represented Hong Kong,” notes Widgery.

There is, nevertheless, an important historical link between the two albums. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the popular culture of jazz-age Shanghai gave way to revolution-inspired art, music, and film. Many popular entertainers, such as Bai Guang, immigrated to Hong Kong—which was then still under British colonial rule—and worked there in the music and film industries.

Retrochine whimsically captures the essence of Hong Kong’s popular culture of the 1950s and 60s as shown through the lens of the Shaw Brothers films, including such songs as the frenetic “Go Go!”. “It follows a different format [from Shanghai Lounge Divas] because it is like a soundtrack to a movie that we never made,” says Widgery. “There are a lot of aspects to it that are not only musical . . . We also had access to dialogues from movies.”

Like Shanghai Lounge Divas before it, Retrochine has enjoyed considerable success, especially in Asia, becoming a top-twenty album in 2010. Time Magazine has hailed it as “fun, edgy, and eclectic,” and its popularity continues, both for the sense of nostalgia that it evokes and for the fresh, contemporary spin that it puts on the Shaw Brothers classics.

A New Dawn for Jazz-Age Shanghai

China, after three decades of significant economic growth and the 1997 re-accessioning of Hong Kong, is undergoing a process of redefining itself, including an official image campaign and a reclaiming of the past. There is even an entire subset of popular culture devoted to “old Shanghai,” encompassing everything from television to restaurants, and so the popularity of Shanghai Lounge Divas in China is not at all surprising.

China, after three decades of significant economic growth and the 1997 re-accessioning of Hong Kong, is undergoing a process of redefining itself, including an official image campaign and a reclaiming of the past. There is even an entire subset of popular culture devoted to “old Shanghai,” encompassing everything from television to restaurants, and so the popularity of Shanghai Lounge Divas in China is not at all surprising.

The Hong Kong-based luxury fashion brand Shanghai Tang adopted Shanghai Lounge Divas as its official in-store soundtrack a few years ago, and in 2010 it released an exclusive album produced by Widgery and Wilson. The Shanghai Tang Lounge Collection features original songs such as “I Like It,” as well as signature Widgery remixes of classic songs like “Crazy Band.”

Despite the key role that he played in launching a global music phenomena, Widgery remains quite humble about his success and gives due credit to the providence of the music. “At the end of the day, the essence comes from the original songs,” he emphasizes. “We tried to rewrite and recreate new things with them. I am only fifty percent of what the work is, and I have always been very aware of that.”

So was it all a matter of destiny? Perhaps so. Had the historical value of the Pathé recordings gone undiscovered and the records and wax cylinders been destroyed, the music might never have reemerged with such popularity. One thing is indeed certain: Widgery gave new life to the voice of Bai Guang and her contemporaries, and in doing so he redefined the sound of jazz-age Shanghai for many years to come.

Experience Jazz-Age Shanghai Online

Shanghai at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

Ling Long Women’s Magazine (1931–1937)

All images courtesy Ian Widgery.